- Blog

- Teaklord

-

Publications

- Books

-

Periodicals

>

- Thailand's 'Lost Kingdom'

- Teak of the Town

- Delve into Thai rice culture

- Book review: The Social Life of Teak

- Conquering Doi Luang Chiang Dao

- A Mindfulness Journey

- Teak Trails

- A Culture Blossoms

- Black, White and Blue

- Deep in the Delta

- Strange Town

- Blissful Bloom

- The Wonder of Water

- Striking Signs

- A Hike up Chiang Dao Mountain

- Quirky Chiang Mai

- Trailblazer

- On the Road to Rio

- Digital content

- Portfolio

- Short Stories

- Biography

Travel

Ron has written travel stories about locations as diverse as Madagascar and Borneo, Venezuela and Vietnam. Yet the most intriguing stories are often right on your doorstep, such as the Avebury stone circle in England.

THE MYSTERIOUS STONES OF AVEBURY

“It (Avebury) does as much exceed in greatness the so reknowned Stonehenge, as a cathedral doeth a parish church.” (John Aubrey, 1649)

The ancient stone circle at Stonehenge in Southwest England is one of the best-known monuments in the world, and is visited by busloads of tourists each day. Yet few people have ever heard of Avebury, another prehistoric site located just half an hour’s drive north of Stonehenge. Avebury is not only older and much bigger than Stonehenge (in fact it’s the biggest stone circle in the world), but it also has a winding, ceremonial avenue leading to it, and nearby are Silbury Hill, the largest man-made mound in Europe, and West Kennet long barrow, the finest megalithic tomb in England and Wales.

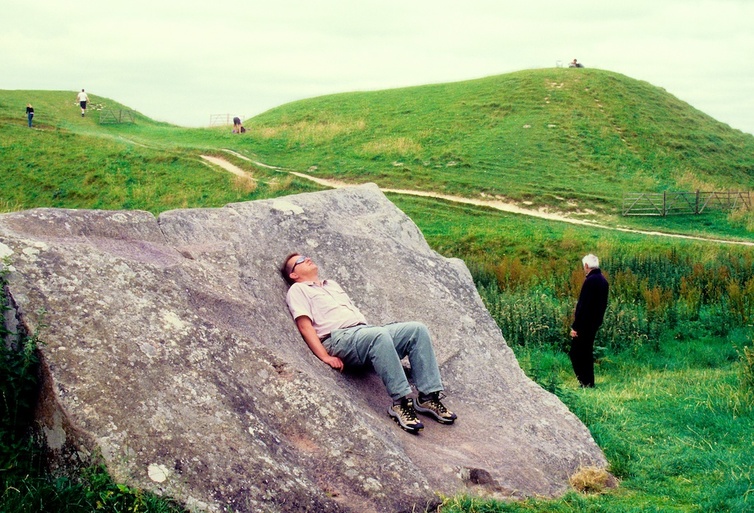

When I entered the Avebury stone circle for the first time, I was confronted by a striking sight. One of the massive stones was leaning slightly inwards, and a man stood leaning against it with his forehead. He did not move from this posture for the next ten minutes, and seemed to be in deep communication with this inanimate object. Such is the power of these stones that have mystified generations of visitors. Though the site has a distinct aura of spirituality, and has often been referred to as a temple, the vast tracts of time that separate us from its builders make it impossible to know its original purpose. Stonehenge is thought to have been constructed as an astronomical observatory, but there is no evidence that Avebury had a similar role, and the most likely explanation is that it was a focus for ceremonies and rituals.

When I entered the Avebury stone circle for the first time, I was confronted by a striking sight. One of the massive stones was leaning slightly inwards, and a man stood leaning against it with his forehead. He did not move from this posture for the next ten minutes, and seemed to be in deep communication with this inanimate object. Such is the power of these stones that have mystified generations of visitors. Though the site has a distinct aura of spirituality, and has often been referred to as a temple, the vast tracts of time that separate us from its builders make it impossible to know its original purpose. Stonehenge is thought to have been constructed as an astronomical observatory, but there is no evidence that Avebury had a similar role, and the most likely explanation is that it was a focus for ceremonies and rituals.

It is impossible to walk around the circle without contemplating the intensive labour involved in constructing it. Most of the standing stones that remain (76 out of an estimated 247 originally) are taller than a man and weigh between 15 and 60 tons. The only conceivable way to move them in the neolithic period would have been on wooden rollers, and the effort of standing them upright must have been gigantic. To give an example, when a smallish stone in Kennet Avenue was being replaced in its original position in 1934, it took 14 men four days to lever it upright. The circle is surrounded by a ditch ten metres deep, and the chalk dug out was used to make a bank on the outside of the ditch that rises about five metres above the height of the circle. This bank might have been used as an amphitheatre for viewing ceremonies within the circle.

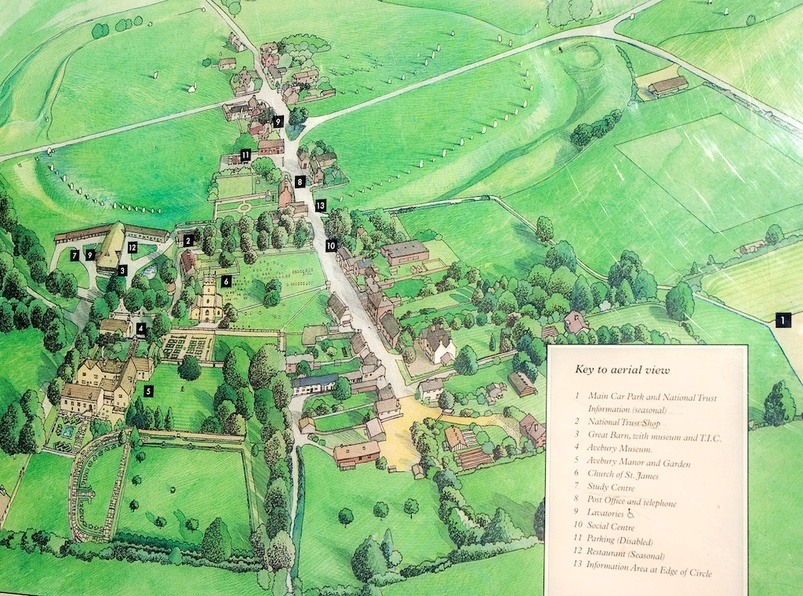

Some people chose to walk along the ridge of the bank, which affords great views of the circle, while others like myself preferred to walk around beside the stones themselves, which is not permitted at Stonehenge. Within the large circle are two smaller circles of stones, as well as part of the village of Avebury and a busy road passing through from north to south. Archaeological digs have shown that the site was ignored by the Romans and Saxons, and it was not until medieval days that a village was built here. Interestingly, however, most of the village, including the church, is located outside the circle, which suggests that the locals did not want to disturb the great work of their ancestors.

Not everyone was so considerate. When Christianity became established in South England during the 13th century, sites like Avebury were seen as the work of the Devil and many of the stones were dragged down and buried or destroyed. This destruction continued intermittently until the 19th century, and one observer, William Stukeley, recounted how a fire was built beside a stone, which was then pushed over and heated. When the stone had become very hot, cold water would be thrown on it, after which it could be smashed with a hard blow from a sledgehammer. Once broken into pieces, many of the stones were used for building houses, but those who sought to profit from the enterprise were unsuccessful. One housing speculator, Tom Robinson, was ruined when his houses burned down in an accidental blaze.

As a result of this destruction, many stones are missing from the circle, particularly on the east side and the inner circles. However, when the monument was finally seen as being of great historical importance, an effort was made to locate those stones which had been buried and re-position them in their original places. The greater part of the re-construction of the site as it is today was done by Alexander Keiller, whose family made a fortune out of marmalade. In the 1930s Keiller purchased the site and meticulously replaced all buried stones in their original positions. His excavations revealed flint arrowheads, broken pots and antlers that were probably used to dig out the chalk from the ditch. These findings are now on display in the Keiller Museum, which along with an interactive display about Avebury makes a good introduction to the site for visitors.

As a result of this destruction, many stones are missing from the circle, particularly on the east side and the inner circles. However, when the monument was finally seen as being of great historical importance, an effort was made to locate those stones which had been buried and re-position them in their original places. The greater part of the re-construction of the site as it is today was done by Alexander Keiller, whose family made a fortune out of marmalade. In the 1930s Keiller purchased the site and meticulously replaced all buried stones in their original positions. His excavations revealed flint arrowheads, broken pots and antlers that were probably used to dig out the chalk from the ditch. These findings are now on display in the Keiller Museum, which along with an interactive display about Avebury makes a good introduction to the site for visitors.

After walking round the perimeter of the huge circle (about 1.3km or nearly a mile), I settled into the Red Lion pub in the centre of the circle to tuck into a steak and ale pie and a refreshing pint of bitter. I then browsed in the Henge Shop at the remarkable number of books that have been written on the subject of stone circles, and noted a few odd beliefs connected with particular stones. For example, the Swindon Stone, which weighs around 60 tons, is thought to spin on its axis at midnight, and running 100 times anti-clockwise round the Devil’s Chair can summon up the Devil himself.

On leaving the main circle, I took a stroll down Kennet Avenue. This is one of two avenues which once led to the stone circle, and it still has an aura of pageantry – I could easily imagine processions, both solemn and joyous, making their way along this 15-metre wide corridor. The rough surface of the stones bordering the avenue, which have not been carved as at Stonehenge, sometimes take on the form of faces or strange creatures, but whether this effect was intended can not be known. Kennet Avenue once led to a place called the Sanctuary, which lies over two kilometres south of the circle, but nothing remains of the southern part of the avenue, and only a few concrete slabs mark the former site of the Sanctuary. Yet there are still a couple of impressive man-made structures in the region that are just as old as Avebury and well worth a look. Both are located beside the modern A4 road that leads from London to Bath.

Silbury Hill is as much a puzzle as the Avebury circle. It stands 40 metres high and 165 metres wide, thus rivalling the Egyptian pyramids in its scale. Some clever mathematician calculated that it would have taken 800 men ten years to build it, though of course we do not know how hard people worked 5000 years ago. Excavations revealed that it was built in three stages, but just why it was built nobody knows. It was always presumed to be a glorified burial chamber for a revered leader, but a much publicized excavation in the 1960s, with TV cameras awaiting the great discovery, produced nothing. It is also unlikely that it was erected for military or astronomical purposes, but whatever the reason for its existence, its massive, symmetrical bulk is a wonder to behold.

Silbury Hill is as much a puzzle as the Avebury circle. It stands 40 metres high and 165 metres wide, thus rivalling the Egyptian pyramids in its scale. Some clever mathematician calculated that it would have taken 800 men ten years to build it, though of course we do not know how hard people worked 5000 years ago. Excavations revealed that it was built in three stages, but just why it was built nobody knows. It was always presumed to be a glorified burial chamber for a revered leader, but a much publicized excavation in the 1960s, with TV cameras awaiting the great discovery, produced nothing. It is also unlikely that it was erected for military or astronomical purposes, but whatever the reason for its existence, its massive, symmetrical bulk is a wonder to behold.

Silbury Hill is right beside the modern road, but it takes a short uphill trek south of the road to get to West Kennet long barrow, which was built at around the same time as the Avebury circle and was used as a burial chamber. The respect in which these people held their ancestors is reflected in the dimensions of the tomb, which is about 100 metres long, six metres high and seven wide. Protected by huge standing stones at the western end are five chambers in which the bones of about 40 people were found. It is possible for visitors to clamber into the barrow and see how the chambers were built, radiating from a central passageway. The situation of the long barrow, on top of a hill with a far-reaching view, seems a particularly appropriate final resting place.

Avebury is just a couple of hours’ drive west of London, and there is no admission to the site, as there is at Stonehenge. The absence of tourist buses adds to the venerable aura of the place, so if you have to choose between the two, go for Avebury. However, since the sites are only half an hour apart, a day spent marvelling over the mysterious stones of Avebury and Stonehenge promises a memorable journey through time to the remotest era of human history.

Avebury is just a couple of hours’ drive west of London, and there is no admission to the site, as there is at Stonehenge. The absence of tourist buses adds to the venerable aura of the place, so if you have to choose between the two, go for Avebury. However, since the sites are only half an hour apart, a day spent marvelling over the mysterious stones of Avebury and Stonehenge promises a memorable journey through time to the remotest era of human history.

|

Text and images copyright © Ron Emmons 2000-2024

Contact details: Ron Emmons 122 Moo 7, San Pisua, Chiang Mai 50300, Thailand. Tel/Fax: (66-53) 115150 Mobile: +66-841758104 [email protected] amazon.com/author/ronemmons |

- Blog

- Teaklord

-

Publications

- Books

-

Periodicals

>

- Thailand's 'Lost Kingdom'

- Teak of the Town

- Delve into Thai rice culture

- Book review: The Social Life of Teak

- Conquering Doi Luang Chiang Dao

- A Mindfulness Journey

- Teak Trails

- A Culture Blossoms

- Black, White and Blue

- Deep in the Delta

- Strange Town

- Blissful Bloom

- The Wonder of Water

- Striking Signs

- A Hike up Chiang Dao Mountain

- Quirky Chiang Mai

- Trailblazer

- On the Road to Rio

- Digital content

- Portfolio

- Short Stories

- Biography