Tracking the Teak Lord

Part three: Fact and Fiction in the novel

Warning: contains spoilers.

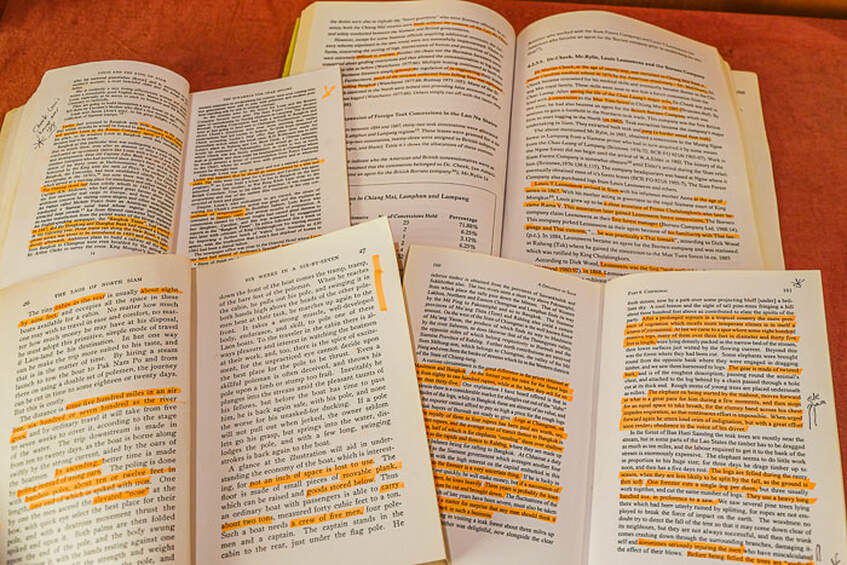

One of the joys of writing fiction rather than non-fiction is that you don’t have to provide documentary evidence of all that happens in the book, as readers expect novels to be written from the imagination, not reality. However, as the saying goes, “truth is stranger than fiction”, and these days a great number of novels are “based on a true story”, as is my own.

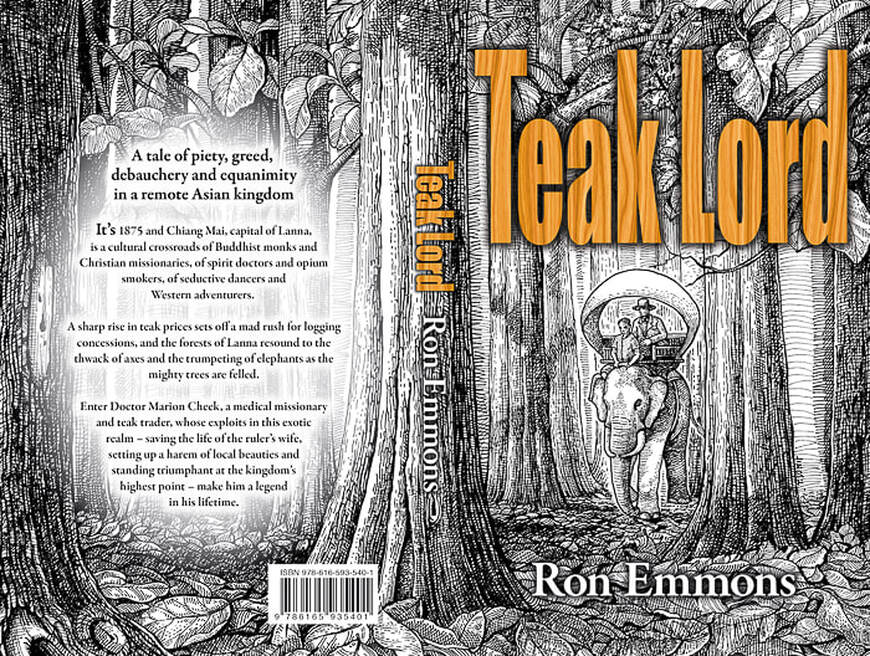

The key phrase here is “based on”, as novelists are free to wander far from that base and create an altogether different version of what really happened. So it was with Teak Lord. For the first three-quarters of the book, I tried to be as true to the characters and events as I could, but for the last quarter, the tale took on a life of its own.

As mentioned in the Author’s Note at the beginning of the novel, I changed the sequence of some incidents to suit the plot, which also led me to give no dates after the opening phrase, placing the start in February 1875. I wanted the relationship between Cheek and Leonowens to be prominent in the story, though in reality, Cheek had been in Chiang Mai nearly ten years before Leonowens arrived. By giving no dates, I was able to introduce Leonowens fairly early in the book.

I took pleasure in the unlikelihood yet veracity of events such as Cheek’s visit to watch spirit doctors performing an exorcism, though in fact this scene is told almost exactly as it was recorded by Cheek himself. Cheek’s saving the life of Chao Inthanon’s wife may also seem unlikely, given local mistrust of his pills and potions, but the event is well documented and proved a key turning point in Cheek’s life, as from then on the Chao showered him with presents, such as a piece of land by the river and the pretty girl Noja, with whom Cheek went on to have an affair.

Since there are no reliable sources of dialogue conducted in those days, I used my imagination to create conversations while trying to be true to the personality of the characters as described by others. Thus the Reverend McGilvary is depicted as pious, Cheek seems greedy, both he and Leonowens are debauched at times, and Phra Prachak aspires to equanimity in all he does.

Phra Prachak is named after a Thai environmentalist monk whose conservation efforts earned him widespread recognition as well as enemies in the 1990s. Other monks who appear in Teak Lord are Ajarn Chah, who was a renowned meditation master of the 20th century, and Phra Dharmakosacarya, another highly revered Thai monk of the 20th century, who is better known by the name Buddhadhasa.

The significance of Buddhism in Teak Lord is probably the biggest deviation from historic reality to my own interests. Early Western visitors to Siam were unanimously “scathing” of Buddhist beliefs, as Cheek mentions in an early chapter of Teak Lord – Meditate for cool heart.

Yet Cheek seemed to be an open-minded character, and I do not think it beyond belief that he would take an interest in Buddhism, though his eventual ordination as a Buddhist monk in Teak Lord is perhaps stretching this point a bit. However, it did enable me to write a ‘feel-good’ ending in which Cheek and McGilvary finally overcome their differences.

In reality, Marion Cheek died, probably of cirrhosis of the liver, in 1895 in the Gulf of Thailand while on his way to Hong Kong for treatment, and now lies in a forgotten grave in the Presbyterian Cemetery in Bangkok.

A strong deviation from historical reality in the plot of Teak Lord begins with the chapter Birth of a Colonial Club, in which Marion Cheek pledges 500 rupees towards the purchase of the land on which the Gymkhana Club was to be built. You might notice that at the end of Part Two of Tracking the Teak Lord, the plaque bearing the names of the founding members of the club does not include Cheek. Since Cheek died in 1895 and the club was not formed until 1898, this is not surprising.

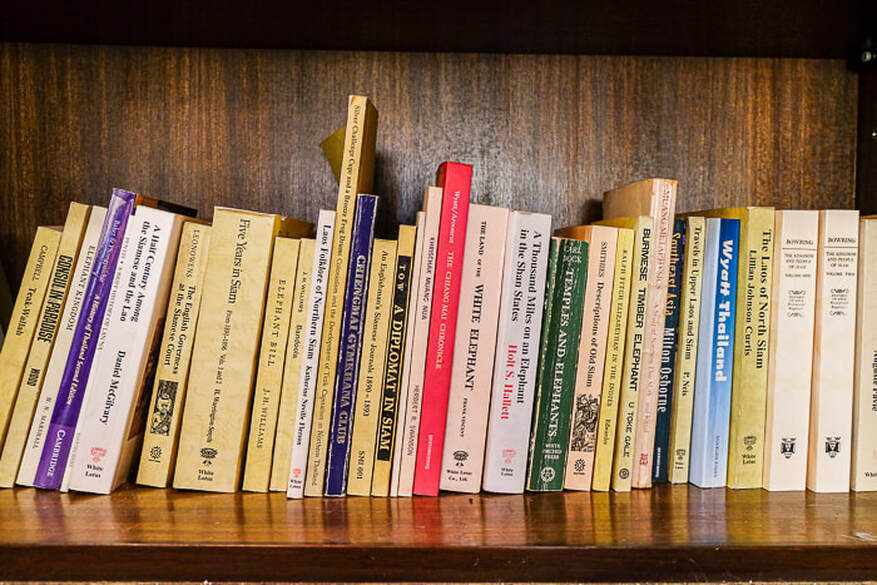

Two other characters grew large in my imagination during the writing of Teak Lord. One was George Woodward, whom I based on the character of Reginald Campbell. Campbell was the author of Teak Wallah, one of the most readable books about teak in Siam/Thailand, written in the 1920s. In chapter 16 of Teak Lord, Of girdling and ounging, Woodward gives a Campbell-like description of the entire teak logging process, from girdling to neaping, two peculiarly teak-related terms.

From photos of him, I imagined Campbell as an extremely proper type who never got dirty, even in the muddy teak forests. I was sad when I had to sacrifice him to allow Cheek an escape route from his predicament of being hounded by the Siamese government.

The other character I grew to like immensely was Harry Stevens, a man of whom I had only read a single reference as a one-time postmaster in Chiang Mai. I wanted a resident foreigner to befriend Cheek and explain some cultural quirks to him, so I developed Stevens as a ‘Cockney sage’ who introduces Cheek to everything from the ‘candlelit walk’ temple ceremony to the work of Charles Darwin and the use of a face mask, which these days is an indispensable piece of equipment for us residents of Chiang Mai in the dry season.

In sum, I hope I have painted a colourful and reasonably accurate portrait of Chiang Mai in the late 19th century, peopled by credible characters who reflect the interests of the era – namely piety, greed, debauchery and equanimity.