- Blog

- Teaklord

-

Publications

- Books

-

Periodicals

>

- Thailand's 'Lost Kingdom'

- Teak of the Town

- Delve into Thai rice culture

- Book review: The Social Life of Teak

- Conquering Doi Luang Chiang Dao

- A Mindfulness Journey

- Teak Trails

- A Culture Blossoms

- Black, White and Blue

- Deep in the Delta

- Strange Town

- Blissful Bloom

- The Wonder of Water

- Striking Signs

- A Hike up Chiang Dao Mountain

- Quirky Chiang Mai

- Trailblazer

- On the Road to Rio

- Digital content

- Portfolio

- Short Stories

- Biography

Biography

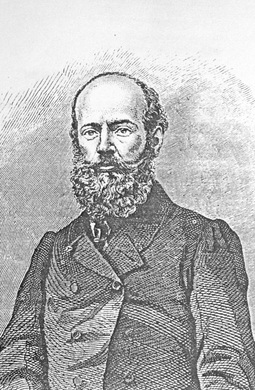

Ron occasionally writes biographies blended with travelogue that reveal an intriguing character as well as places that are associated with him or her. Henri Mouhot was a French naturalist who popularised Angkor Wat.

IN MOUHOT'S FOOTSTEPS

“At Ongcor, there are ...ruins of such grandeur... that, at the first view, one is filled with profound admiration, and cannot but ask what has become of this powerful race, so civilized, so enlightened, the authors of these gigantic works?”

(Henri Mouhot, 1826-1861)

(Henri Mouhot, 1826-1861)

|

Let’s get one thing straight - Henri Mouhot did not discover Angkor Wat. Yet he is widely credited with popularising the place in the imagination of westerners, partly through comments such as that above. Though several other Europeans had been there and written about it before, none managed to describe it as evocatively as Mouhot did, in both words and delightful sketches. The fact that he had already perished in the jungles of Laos before the publication of his book ‘Travels in Siam, Cambodia and Laos’ in 1864 only served to increase interest. Since then, thousands have followed in his footsteps to marvel over the beatific Buddhas in the Cambodian forest, though few have experienced such hardships as Mouhot did on his daring expeditions into largely uncharted territory. |

Mouhot was born in 1826 in Montbeliard, France, near the Swiss border, and from an early age his thirst for knowledge drove him to travel. He spent about ten years in Russia working as a language tutor, then immersed himself in the study of natural science. In 1856 he married a daughter of Mungo Park, an English explorer, and went to live in Jersey. However, within a year he came across a book on Siam (‘The Kingdom and People of Siam’ by Sir James Bowring, published in 1857) that made him determined to conduct a botanical expedition in Southeast Asia. With the support of the Geographical and Zoological Societies in London, he set out to Bangkok in 1858, and over the next three years made four journeys into the interior. It was the second and fourth of these that made him famous, both for his visit to Angkor and for his exploration of previously-unknown Laos.

While Mouhot lived during an era of colonial expansion, he was broad-minded enough to doubt the beneficial effects of the European colonisers, and his journal is peppered with such interesting reflections. “Will the present movement of the nations of Europe towards the East result in good by introducing into these lands the blessings of our civilization? Or shall we, as blind instruments of boundless ambition, come hither as a scourge, to add to their present miseries?” Though his expeditions were planned around collecting new zoological specimens, he frequently diverges in his journal to comment on the deeper implications of his travels.

On his first journey, he sailed up the Chao Phraya River from Bangkok to Ayuthaya, former capital of Siam, and immediately encountered the constant scourge of his Asian travels – mosquitoes, or, in Mouhot’s words, ‘those pestilent little vampires’. Later on, he would meet fiercer adversaries, such as tigers, leopards, rhinoceros, crocodiles, scorpions, centipedes, and armies of leeches. Of these blood-suckers, he commented “Often my white trousers are dyed as red as those of a French soldier”. Fortunately, Mouhot was extremely resilient, and managed to avoid any serious illnesses. He attributed his good health to “abstinence, all but total, from wine and spirits, and drinking only tea”.

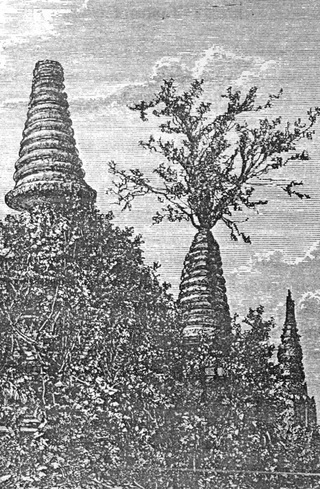

He wrote little in his journal of the evocative ruins of Ayuthaya, though his sketches show how they have hardly changed in the intervening years. Since the site is now maintained by the Thai government’s Fine Arts Department, it is easier for modern-day visitors to get around and admire the slender stupas and the battered Buddhas of what was one of the world’s most sophisticated kingdoms in its 15th-16th century heyday. The city was razed by the Burmese in the mid-18th century, but is still considered by many to have been the cradle of Siamese culture.

On this ‘acclimatising’ expedition, Mouhot continued a little further north to Mount Prabat, marvelling at the lush countryside and having frequent encounters with wild animals. On one occasion he shot a leopard that had been stealing his party’s dogs and pigs, and on another had to take refuge in a tree for a night to escape the attentions of a hungry tiger.

In December 1858, Mouhot set out on his second and longest journey, which lasted till April 1860 and included three weeks of detailed observations at Angkor, then known as Ongcor. Once again, the journey was far from pleasant. While recovering at Chanthaburi from an infected cut in his foot, he remarked that, “great spiders and other disgusting creatures, crawling about under the roof, would startle me by dropping on my face.”

On this ‘acclimatising’ expedition, Mouhot continued a little further north to Mount Prabat, marvelling at the lush countryside and having frequent encounters with wild animals. On one occasion he shot a leopard that had been stealing his party’s dogs and pigs, and on another had to take refuge in a tree for a night to escape the attentions of a hungry tiger.

In December 1858, Mouhot set out on his second and longest journey, which lasted till April 1860 and included three weeks of detailed observations at Angkor, then known as Ongcor. Once again, the journey was far from pleasant. While recovering at Chanthaburi from an infected cut in his foot, he remarked that, “great spiders and other disgusting creatures, crawling about under the roof, would startle me by dropping on my face.”

To Mouhot, such inconveniences were sufferable for the thrill of reaching Angkor Wat, now known to be the largest temple in the world. He called it “a rival to that of Solomon, and erected by some ancient Michael Angelo”. After “making no pretension whatever to architectural or archaeological acquirements”, Mouhot goes on to give precise descriptions, compass directions and measurements of balconies and ballustrades, of galleries and porticos, of columns and cornices. His detailed descriptions of the bas relief carvings in the galleries around the lower level of Angkor Wat must have stirred the imagination of his contemporaries, with mention of warriors mounted on tigers, angels carried by griffins and people entering Paradise. “These bas reliefs are perfect; the rest are inferior in workmanship and expression.” Mouhot pronounced, and all experts on stone carvings who have seen them concur that they have no equal.

Sometimes Mouhot appears to be a super-explorer, rising to each challenge he faces with precision and exactitude. His character becomes all the more endearing, however, when he shows himself human and capable of error. He could not resist making a guess that the temples at Angkor dated back over two millennia, though it is now known that the dates of Angkor’s habitation were from the early 9th to the early 15th centuries, making the site just over a thousand years old. He also reveals his Victorian context by describing the Buddha heads that surmount the gateways to Angkor Thom as “four immense heads in the Egyptian style”. In those days it was popular to ascribe the origin of all civilization to the Middle East.

As with the ruins of Ayuthaya, the scene has changed little at Angkor since Mouhot visited, and his descriptions generally hold true. One significant difference is that due to easy access, now thousands of visitors explore the site each day. One of the most popular locations, especially at sunset, is Mount Bakheng, set northwest of Angkor Wat and just south of Angkor Thom. The steep climb to the peak (about 70 metres high) is rewarded with a magnificent view of the towers of Angkor Wat and lush countryside stretching into the distance. Mouhot wrote of it, “All this region is now as lonely and deserted as it must have been full of life and cheerfulness; and the howling of wild animals, and the cries of a few birds, alone disturb the solitude.” By contrast, today’s visitor must ward off armies of souvenir vendors and jostle with other tourists to get a good photo of the scene.

As with the ruins of Ayuthaya, the scene has changed little at Angkor since Mouhot visited, and his descriptions generally hold true. One significant difference is that due to easy access, now thousands of visitors explore the site each day. One of the most popular locations, especially at sunset, is Mount Bakheng, set northwest of Angkor Wat and just south of Angkor Thom. The steep climb to the peak (about 70 metres high) is rewarded with a magnificent view of the towers of Angkor Wat and lush countryside stretching into the distance. Mouhot wrote of it, “All this region is now as lonely and deserted as it must have been full of life and cheerfulness; and the howling of wild animals, and the cries of a few birds, alone disturb the solitude.” By contrast, today’s visitor must ward off armies of souvenir vendors and jostle with other tourists to get a good photo of the scene.

Thanks to foresight of the archaeologists who cleared the jungle around Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom, modern visitors can still appreciate the interaction of Nature with these ancient edifices at Ta Phrom, a large temple complex situated to the east of Angkor Thom. This particular temple was left in its natural state, and Mouhot’s comment on it remains true today: “an exuberant vegetation has overgrown everything, galleries and towers, so that it is difficult to force a passage.” The crowning glory of the ‘exuberant vegetation’ are the towering fig and silk-cotton trees, many of which straddle the walls of the temple and spread their roots in a vice-like grip on the stones. For many visitors, this aspect of Angkor is what remains indelibly in the mind.

After 15 months on the move, sleeping rough and eating little apart from rice and dried fish, Mouhot was overjoyed to return to the city and its comforts. “Bangkok had never looked so beautiful”, he reflected, a comment which might draw wry smiles from modern readers, wondering how he would react to today’s metropolis with its traffic-choked streets and towering skyscrapers. Yet disaster lay in wait for him. He carefully boxed up all his collections of insect specimens, many of them irreplaceable, that had taken countless hours of locating and identifying, but the steamer on which they were being shipped back to Europe foundered in Singapore harbour and everything was lost.

Mouhot’s third journey was a brief trip to Petchaburi in 1860, then he faced seemingly unsurmountable problems in his attempt to travel north into Laos. He set out in October 1860, only to be refused permission to go further north by an official at Chaiyaphum, and returned to Bangkok in February 1861. Finally his persistence paid off and in July 1861 he entered Luang Phabang, the former royal capital of Laos, which he found “a delightful little town” (as most modern visitors still do). He would certainly have had no previous accounts on which to base his expectations. As he wrote, “To consult any existing maps of Indo-China for my guidance in the interior of Laos would have been a folly, no traveller, at least to my knowledge, having penetrated into east Laos, or published any authentic information respecting it.”

After 15 months on the move, sleeping rough and eating little apart from rice and dried fish, Mouhot was overjoyed to return to the city and its comforts. “Bangkok had never looked so beautiful”, he reflected, a comment which might draw wry smiles from modern readers, wondering how he would react to today’s metropolis with its traffic-choked streets and towering skyscrapers. Yet disaster lay in wait for him. He carefully boxed up all his collections of insect specimens, many of them irreplaceable, that had taken countless hours of locating and identifying, but the steamer on which they were being shipped back to Europe foundered in Singapore harbour and everything was lost.

Mouhot’s third journey was a brief trip to Petchaburi in 1860, then he faced seemingly unsurmountable problems in his attempt to travel north into Laos. He set out in October 1860, only to be refused permission to go further north by an official at Chaiyaphum, and returned to Bangkok in February 1861. Finally his persistence paid off and in July 1861 he entered Luang Phabang, the former royal capital of Laos, which he found “a delightful little town” (as most modern visitors still do). He would certainly have had no previous accounts on which to base his expectations. As he wrote, “To consult any existing maps of Indo-China for my guidance in the interior of Laos would have been a folly, no traveller, at least to my knowledge, having penetrated into east Laos, or published any authentic information respecting it.”

He had read one estimate of the population of Luang Phabang to be in the region of 80,000, which he immediately revised to a tenth of that figure, as it remains to this day. Situated on a phallic-shaped spur of land at the confluence of the Mekong and Nam Khan Rivers, it is so compact that it is easy to visit its ancient temples on foot. The most striking of all is Wat Xiang Thong (originally built in 1560), with its eaves swooping to the ground, colourful mosaics on the Red Chapel, and sensual carvings on the Funerary Carriage Hall. Mouhot found the people affable and intelligent, and was received with great pomp by the local king. Today Luang Phabang offers a relaxing and welcoming haven to visitors, such that their numbers are constantly on the rise.

He felt proud of the great number of new species he had collected, and wrote rather poignantly that “...even if destined here to meet my death, I would not change my lot for all the joys and pleasures of the civilized world.” Even more poignantly, he noted his future plans: “ ...next January or March I will try to go north or east,...and go down the Mekong in July or August 1862.” Sadly, it was not to be. Though by now Mouhot must have felt himself indestructible, having survived every type of tropical hardship, he succumbed to a sudden fever, perhaps caused by malaria, and died in October 1861. One of his last journal entries recounts a rhinoceros hunt, in which a village chief reserved the honour of finishing off the beast for Mouhot.

Yet perhaps Mouhot’s greatest achievement, beyond his bravery as a fearless explorer and scientific skill as a naturalist, was his ability to establish deep and genuine relationships with almost everyone he met, from kings to missionaries to villagers. He wrote of tears of sadness when one of his servants, Song, left him in Luang Phabang to return to Bangkok, worrying for the young man’s safety. The dedication of his favourite servant, Phrai, is shown by the fact that he somehow managed to transport all of Mouhot’s journals and specimens back to Bangkok, from where they were shipped to Europe. Needless to say, without such devotion, the name of Henry Mouhot would now be lost to the world, and his tomb on the banks of the Nam Khan River near Luang Phabang would be as overgrown as any forgotten temple.

He felt proud of the great number of new species he had collected, and wrote rather poignantly that “...even if destined here to meet my death, I would not change my lot for all the joys and pleasures of the civilized world.” Even more poignantly, he noted his future plans: “ ...next January or March I will try to go north or east,...and go down the Mekong in July or August 1862.” Sadly, it was not to be. Though by now Mouhot must have felt himself indestructible, having survived every type of tropical hardship, he succumbed to a sudden fever, perhaps caused by malaria, and died in October 1861. One of his last journal entries recounts a rhinoceros hunt, in which a village chief reserved the honour of finishing off the beast for Mouhot.

Yet perhaps Mouhot’s greatest achievement, beyond his bravery as a fearless explorer and scientific skill as a naturalist, was his ability to establish deep and genuine relationships with almost everyone he met, from kings to missionaries to villagers. He wrote of tears of sadness when one of his servants, Song, left him in Luang Phabang to return to Bangkok, worrying for the young man’s safety. The dedication of his favourite servant, Phrai, is shown by the fact that he somehow managed to transport all of Mouhot’s journals and specimens back to Bangkok, from where they were shipped to Europe. Needless to say, without such devotion, the name of Henry Mouhot would now be lost to the world, and his tomb on the banks of the Nam Khan River near Luang Phabang would be as overgrown as any forgotten temple.

|

Text and images copyright © Ron Emmons 2000-2024

Contact details: Ron Emmons 122 Moo 7, San Pisua, Chiang Mai 50300, Thailand. Tel/Fax: (66-53) 115150 Mobile: +66-841758104 [email protected] amazon.com/author/ronemmons |

- Blog

- Teaklord

-

Publications

- Books

-

Periodicals

>

- Thailand's 'Lost Kingdom'

- Teak of the Town

- Delve into Thai rice culture

- Book review: The Social Life of Teak

- Conquering Doi Luang Chiang Dao

- A Mindfulness Journey

- Teak Trails

- A Culture Blossoms

- Black, White and Blue

- Deep in the Delta

- Strange Town

- Blissful Bloom

- The Wonder of Water

- Striking Signs

- A Hike up Chiang Dao Mountain

- Quirky Chiang Mai

- Trailblazer

- On the Road to Rio

- Digital content

- Portfolio

- Short Stories

- Biography