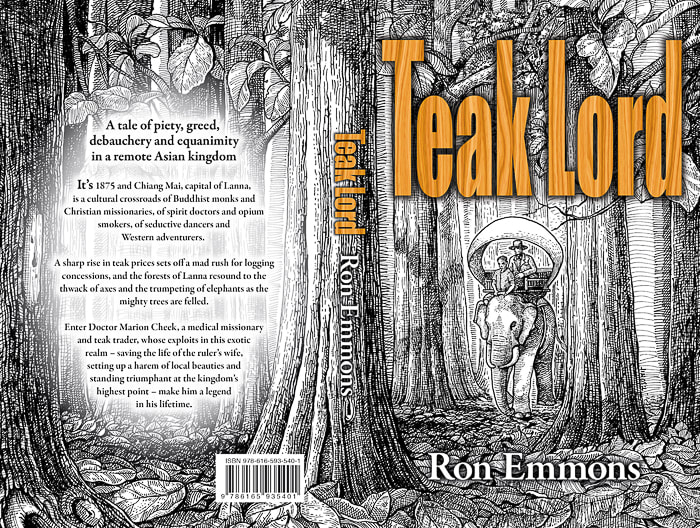

Teak Lord

A novel by Ron Emmons

A tale of piety, greed, debauchery and equanimity in a remote Asian kingdom

It’s 1875 and Chiang Mai, capital of Lanna, is a cultural crossroads of Buddhist monks and Christian missionaries, of spirit doctors and opium smokers, of seductive dancers and Western adventurers.

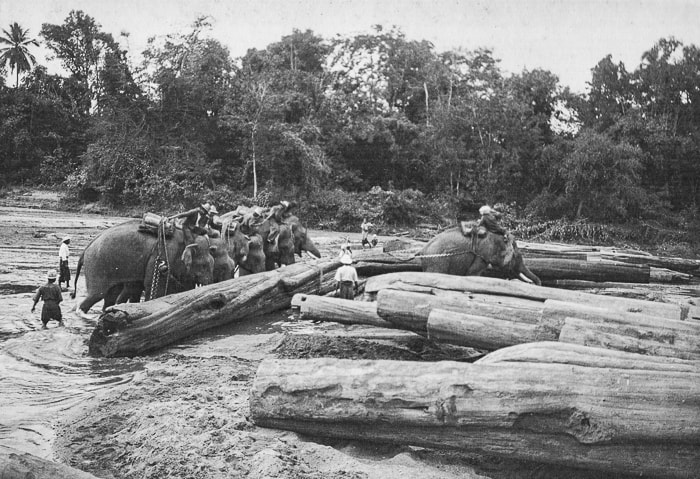

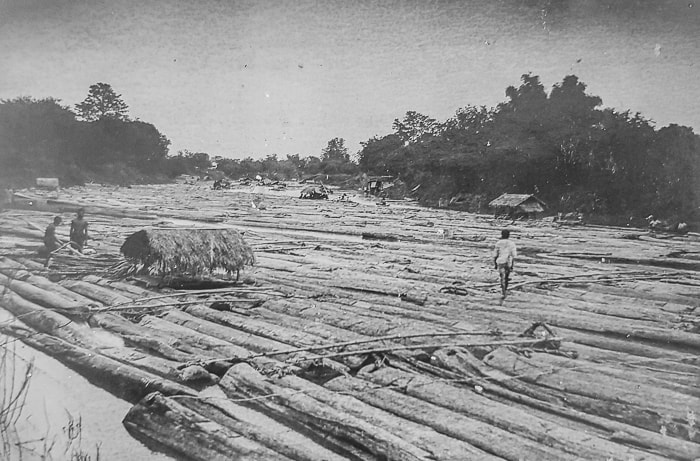

A sharp rise in teak prices sets off a mad rush for logging concessions, and the forests of Lanna resound to the thwack of axes and the trumpeting of elephants as the mighty trees are felled.

Enter Doctor Marion Cheek, a medical missionary and teak trader, whose exploits in this exotic realm – saving the life of the ruler’s wife, setting up a harem of local beauties, and standing triumphant at the kingdom’s highest point – make him a legend in his lifetime.

Besides the mercurial Dr. Cheek, we meet the Reverend McGilvary, a zealous missionary; Louis Leonowens, Cheek's best friend and business adversary; Chao Inthanon, the mischievous and fun-loving ruler of Lanna; Noja, an alluring temptress; Harry Stevens, the Cockney sage of Chiang Mai; Phra Prachak, a constant fount of Buddhist wisdom; George Woodward, a forest manager destined to live in the jungle; and not forgetting Mae Noi and Look Bah, two endearing elephants who accompany Cheek on his adventures through the forests of Lanna.

A sharp rise in teak prices sets off a mad rush for logging concessions, and the forests of Lanna resound to the thwack of axes and the trumpeting of elephants as the mighty trees are felled.

Enter Doctor Marion Cheek, a medical missionary and teak trader, whose exploits in this exotic realm – saving the life of the ruler’s wife, setting up a harem of local beauties, and standing triumphant at the kingdom’s highest point – make him a legend in his lifetime.

Besides the mercurial Dr. Cheek, we meet the Reverend McGilvary, a zealous missionary; Louis Leonowens, Cheek's best friend and business adversary; Chao Inthanon, the mischievous and fun-loving ruler of Lanna; Noja, an alluring temptress; Harry Stevens, the Cockney sage of Chiang Mai; Phra Prachak, a constant fount of Buddhist wisdom; George Woodward, a forest manager destined to live in the jungle; and not forgetting Mae Noi and Look Bah, two endearing elephants who accompany Cheek on his adventures through the forests of Lanna.

HOW TO BUY OR REVIEW

TEAK LORD

BUY:

– Read it for free on Kindle Unlimited

– Buy the ebook on Amazon ($4.99).

– Buy the paperback ($12.99) and hardback ($17.99) on Amazon

BUY IN THAILAND:

– (For residents of Thailand only) Buy a paperback (B400) or

hardback(B500) version (postage included): through LINE (ronemmons), WHATSAPP (0841758104), MESSENGER (FB.com/ron.emmons.56) or EMAIL ([email protected]). Please send a mailing address.

REVIEW:

– Review Teak Lord on Amazon or Goodreads

– Send Ron an email with comments

– Read it for free on Kindle Unlimited

– Buy the ebook on Amazon ($4.99).

– Buy the paperback ($12.99) and hardback ($17.99) on Amazon

BUY IN THAILAND:

– (For residents of Thailand only) Buy a paperback (B400) or

hardback(B500) version (postage included): through LINE (ronemmons), WHATSAPP (0841758104), MESSENGER (FB.com/ron.emmons.56) or EMAIL ([email protected]). Please send a mailing address.

REVIEW:

– Review Teak Lord on Amazon or Goodreads

– Send Ron an email with comments

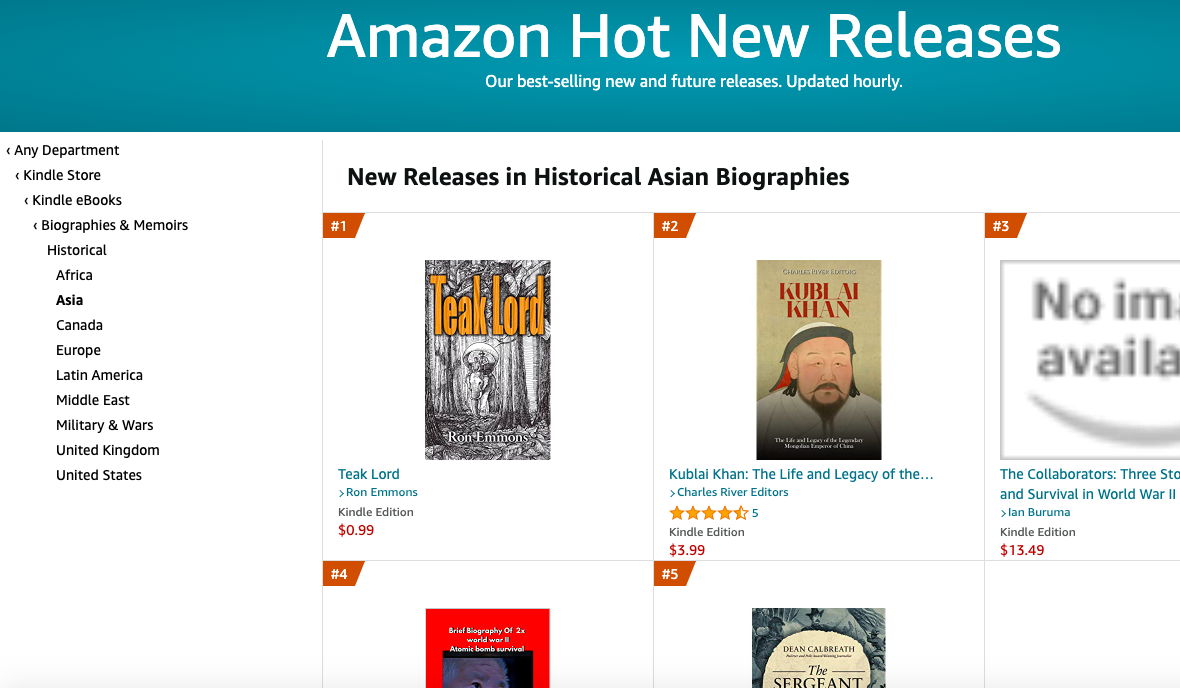

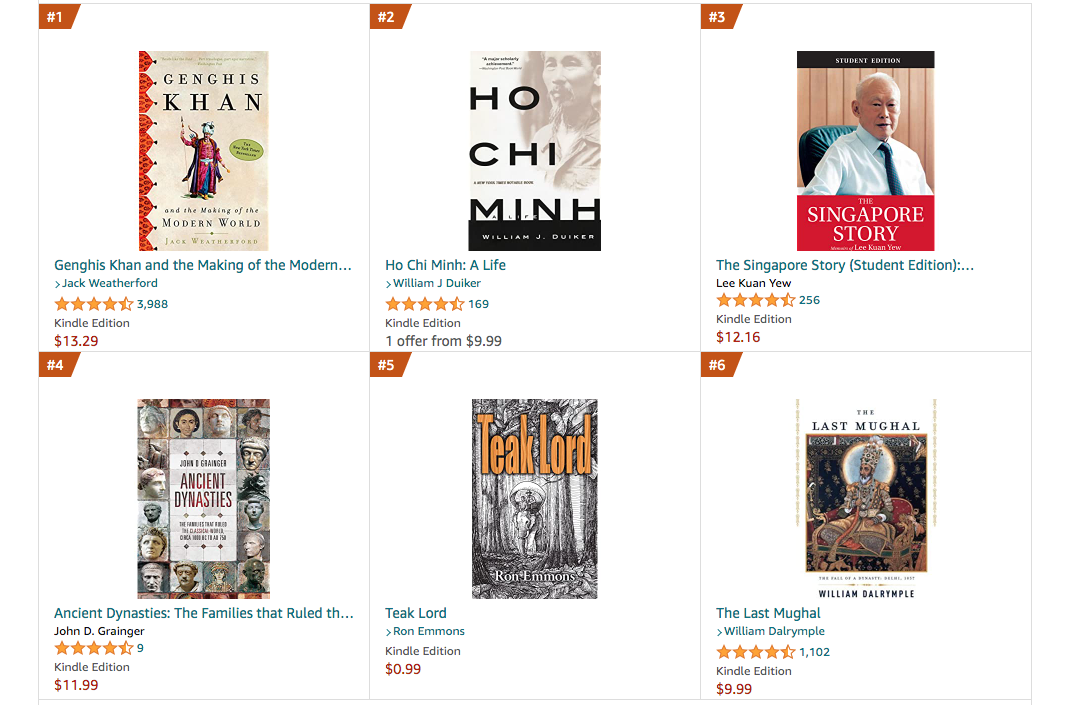

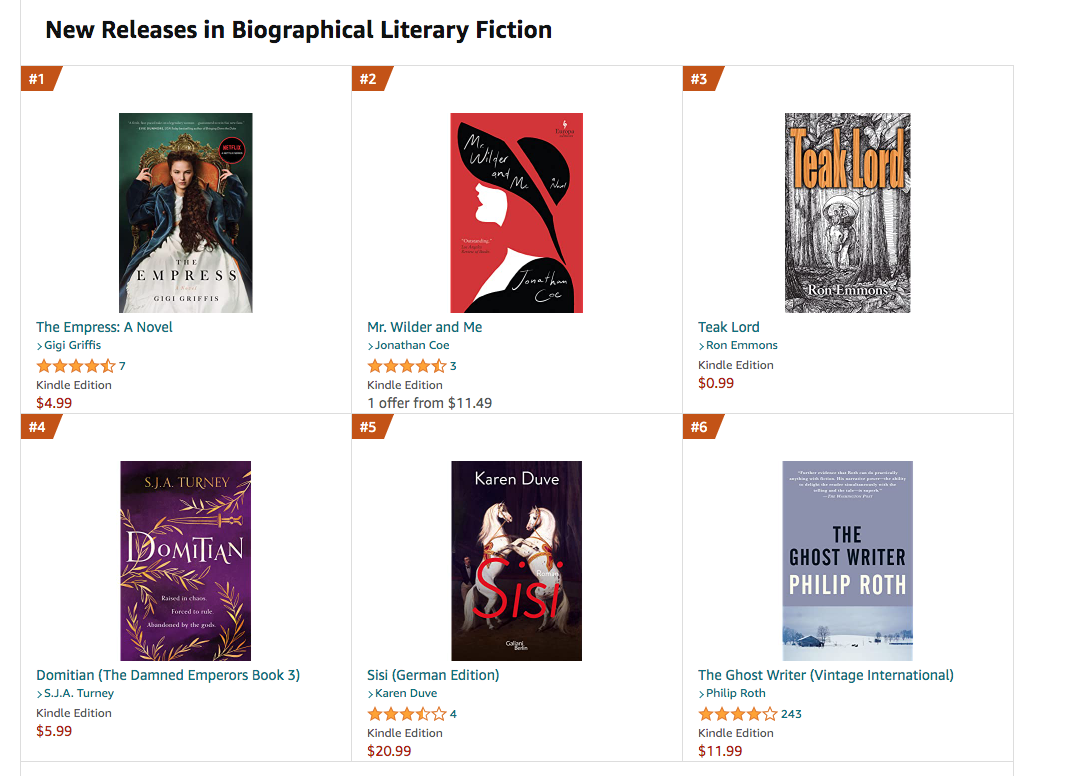

Early Success for Teak Lord!

#1 in New Releases in Historical Asian Biographies

Above William Dalrymple in Historical Asian Biographies!

And above Philip Roth in Biographical Literary Fiction!

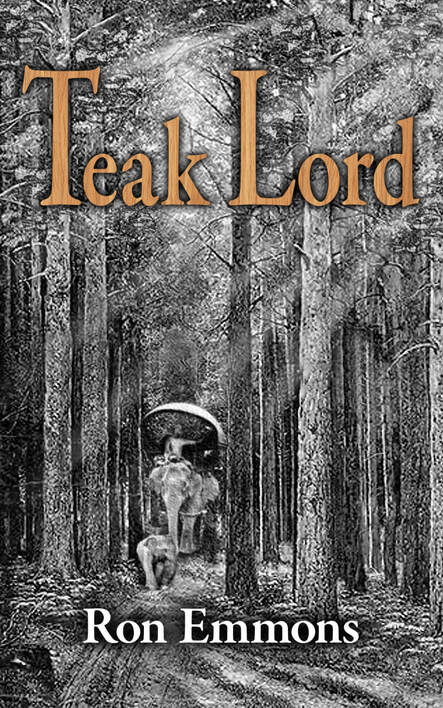

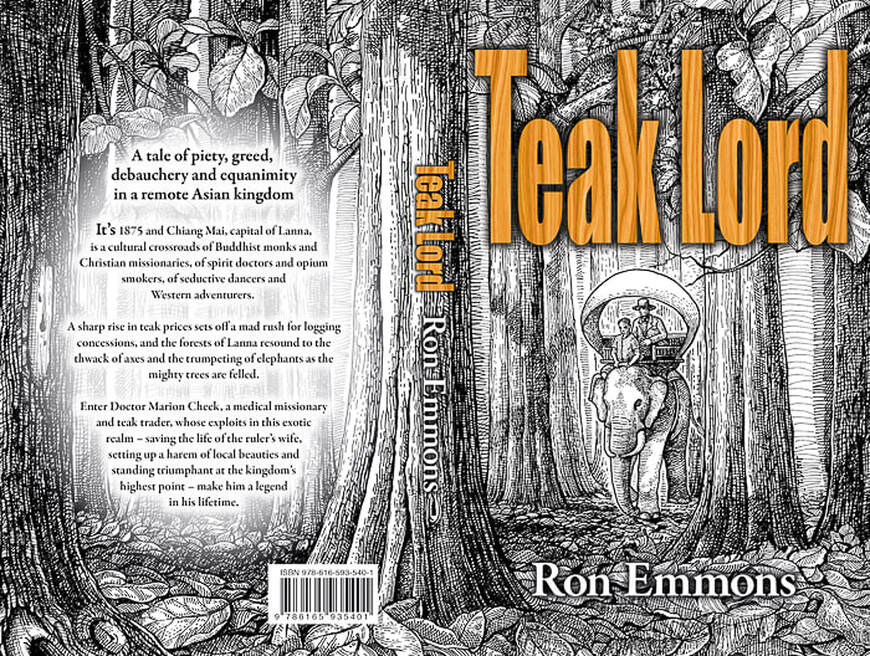

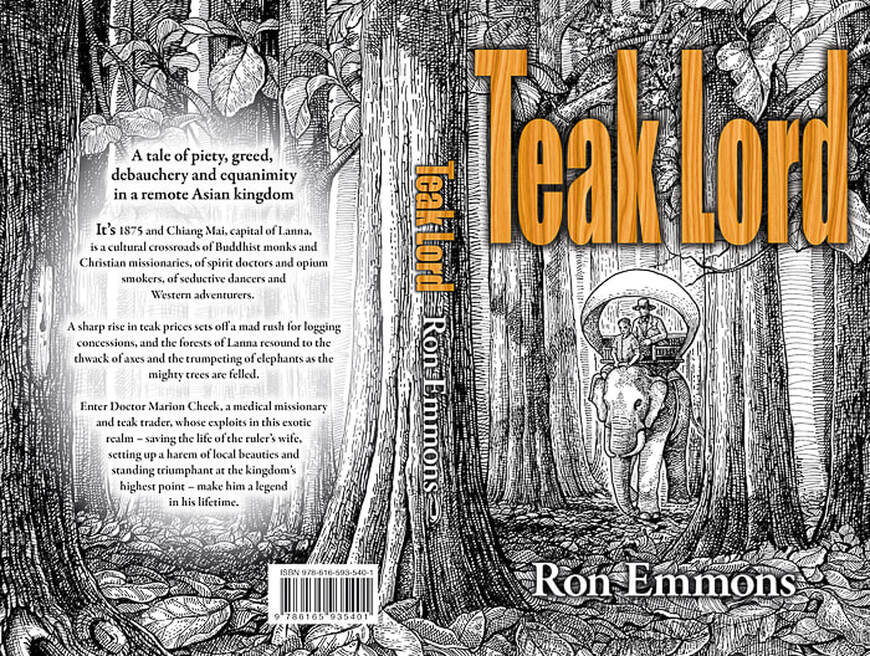

The Making of a Book Cover

They say “You can’t judge a book by its cover”, but you and I know that we DO judge books by their cover when looking for something new to read. Whether you’re browsing the shelves of a bookshop, or scrolling through your favourite categories on Amazon, it’s almost certain you won’t flip the book over (in a bookshop) or flip your eyes right (on Amazon) to read the blurb unless something about the title or cover design intrigues or appeals to you.

In the run-in to self-publishing my novel Teak Lord, I read lots about the importance of covers and started looking at the covers of hundreds of new releases. Most of them had the title in huge capitals and abstract blotches of colour in the background. Very arty, maybe, but this approach does nothing for me. “I know” I thought,” I’ll make my cover as different as I can from those I’m looking at now.”

In the run-in to self-publishing my novel Teak Lord, I read lots about the importance of covers and started looking at the covers of hundreds of new releases. Most of them had the title in huge capitals and abstract blotches of colour in the background. Very arty, maybe, but this approach does nothing for me. “I know” I thought,” I’ll make my cover as different as I can from those I’m looking at now.”

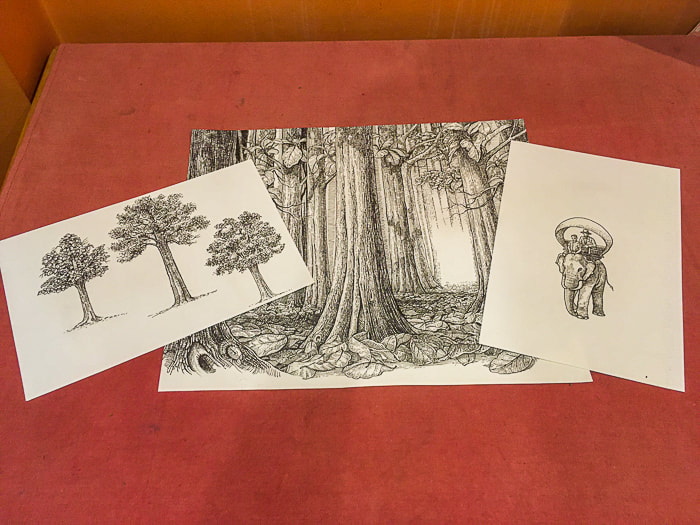

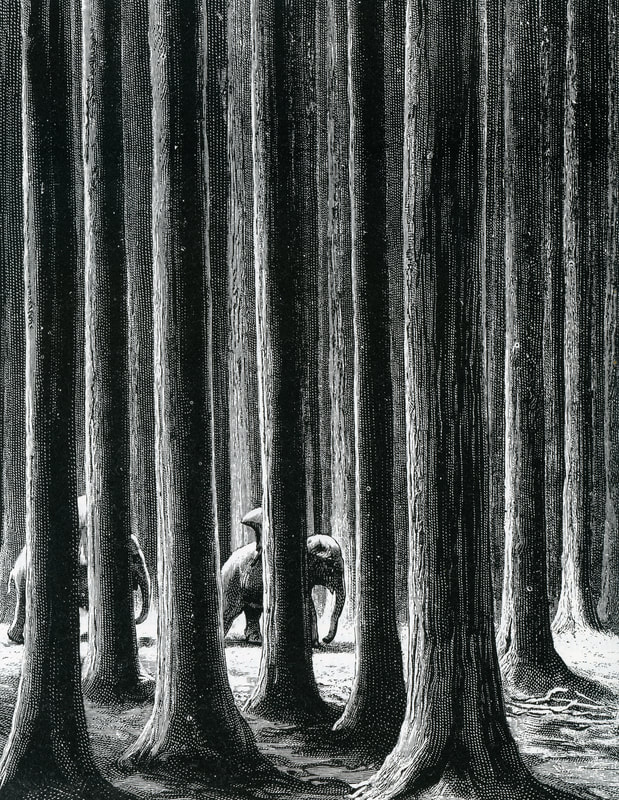

I liked the ink sketches by Eugene Bernand in a book titled Travels in Upper Laos and Siam by French explorer Doctor Neis, which coincided with the time frame of my novel, and one minimalist image by Bernand in particular appealed to me. It was of towering teak trees with huge girths, giant versions of teak elsewhere, with a glimpse of elephants walking in the distance. Neis described the scene thus: “One traveled in these forests as between the pillars of a gigantic temple.” I had appropriated Neis’ wonder at the scene (though not his words!) for a similar description in Teak Lord.

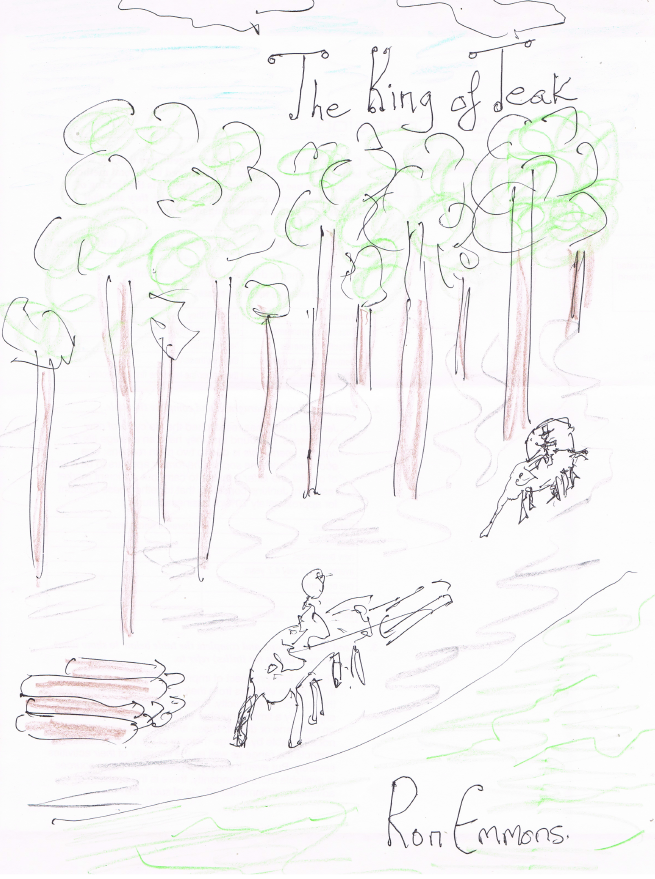

Chairat, head of the team at Within Design, who I had contracted to design a cover, also liked the Bernand image, so that was our starting point. I’m hopeless at drawing, but I scrawled a childish picture of a teak forest beside a river, with elephants (I know, I’m not too good at elephants) pulling logs to give an idea of what content I wanted on the cover. At that stage the working title was The King of Teak.

Chairat thought this image was too ‘busy’, so his illustrator began with a clip-art image showing only forest, elephants and a mahout (elephant handler). I asked for the title to be written in tall letters to echo the tall, straight trees, and I liked the fact that it stood out boldly and was picked out with a vertical wood grain effect. The clip-art trees looked more like pines so I asked Chairat to make sure some big teak leaves were prominent in the image.

Next came the illustrator’s initial sketch of the front and back covers, with plenty of forest on the left where we could superimpose the blurb for the book. I particularly liked that a huge tree ran the length of the spine and conveniently divided the image.

I remembered my description in Teak Lord of Doctor Cheek passing through the Mae Lao forest near the end of Section 34 – Railway Dreams: “An utter silence surrounded them as the elephants padded over a carpet of huge teak leaves and between the massive boles”. I asked the illustrator to make a carpet of leaves, which he duly provided.

I remembered my description in Teak Lord of Doctor Cheek passing through the Mae Lao forest near the end of Section 34 – Railway Dreams: “An utter silence surrounded them as the elephants padded over a carpet of huge teak leaves and between the massive boles”. I asked the illustrator to make a carpet of leaves, which he duly provided.

I had not set out with the intention of finding a cover image that seemed to exactly reflect the words in the book, but neither had I known how the Teak Lord tale would end as I was writing it. Sometimes it’s best when these things just happen of their own accord. In any case I’m pleased with the Teak Lord cover, and hope it draws curious readers into a web of mystery inside.

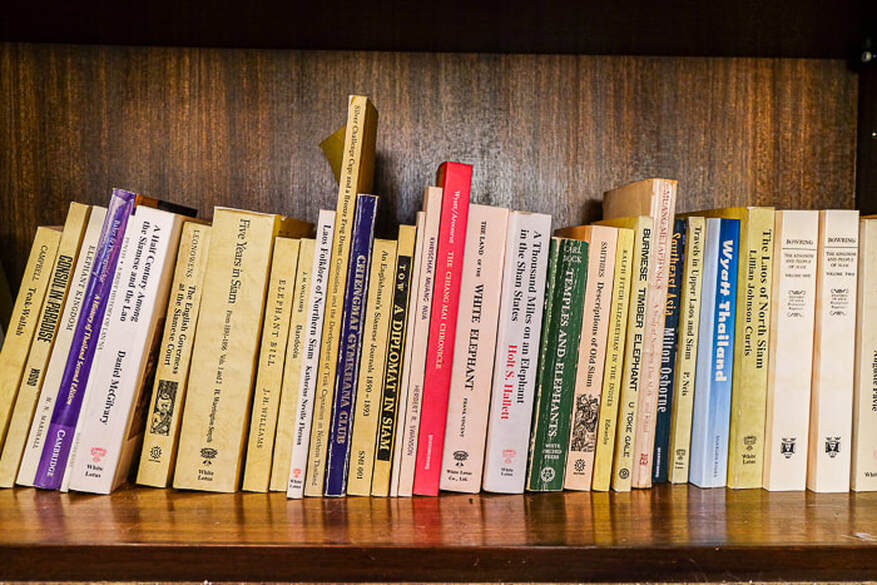

Tracking the Teak Lord

Part one: The tree, the history and the characters

For anyone curious about the main features of a teak tree, how teak logs were worked by elephants or what the main characters in Teak Lord looked like, I’ve put together this brief overview.

The tree

Teak (tectona grandis) is one of the world’s most expensive woods for good reason. Its slow growth makes it incredibly solid and durable, though it is classed only as a medium-hard wood, which also makes it workable for carvers. The presence of silica deters most wood-eating insects, including termites, which can reduce to dust a wooden desk made of a different wood if given the chance.

The most prominent characteristics of the teak tree are its enormous leaves – often as big as elephants’ ears – and its trunk, which grows straighter than virtually any other tree. Though it grows upwards quite quickly, it takes decades for its trunk to grow outward, so loggers need to wait until a tree is at least 50 years old before there’s enough wood to make it worth cutting down.

The history

Teak trading in Siam and Lanna began in earnest after the signing of the Bowring Treaty in 1855, which removed prohibitive taxes from such produce. At this time, Britannia really did ‘rule the waves’, as the song goes, and the demand by colonial powers for wood to make boats was huge. Already teak logging operations were in full swing in North India and Burma, and teak trading companies wasted no time in securing logging concessions in Lanna.

The teak boom really took off in 1882 when a Danish sailor by the name of Anderson sold a shipment of teakwood in England for double the expected price. Once word got around about this, teak traders increased their efforts to fell as many trees as possible, and even though the logging cycle took at least five years from girdling to the sawmill, those involved in the trade saw their wealth increase rapidly.

The most prominent characteristics of the teak tree are its enormous leaves – often as big as elephants’ ears – and its trunk, which grows straighter than virtually any other tree. Though it grows upwards quite quickly, it takes decades for its trunk to grow outward, so loggers need to wait until a tree is at least 50 years old before there’s enough wood to make it worth cutting down.

The history

Teak trading in Siam and Lanna began in earnest after the signing of the Bowring Treaty in 1855, which removed prohibitive taxes from such produce. At this time, Britannia really did ‘rule the waves’, as the song goes, and the demand by colonial powers for wood to make boats was huge. Already teak logging operations were in full swing in North India and Burma, and teak trading companies wasted no time in securing logging concessions in Lanna.

The teak boom really took off in 1882 when a Danish sailor by the name of Anderson sold a shipment of teakwood in England for double the expected price. Once word got around about this, teak traders increased their efforts to fell as many trees as possible, and even though the logging cycle took at least five years from girdling to the sawmill, those involved in the trade saw their wealth increase rapidly.

Eventually the Siamese government saw foreign trading companies as a hindrance to their own economic development and began their own logging operations, overseen initially by Marion Cheek. Firms like the Borneo Company, the Bombay Burmah Trading Company and the East Asiatic Company continued operations well into the 20th century, though they were gradually squeezed out until by the mid-20th century, Thailand controlled all the logging within the country.

The characters

Most of the characters in Teak Lord are based on real, historical people, although as I mention in the Author’s Note, I have taken liberties with their thoughts and actions, while attempting to portray characteristics that were noted by writers at the time.

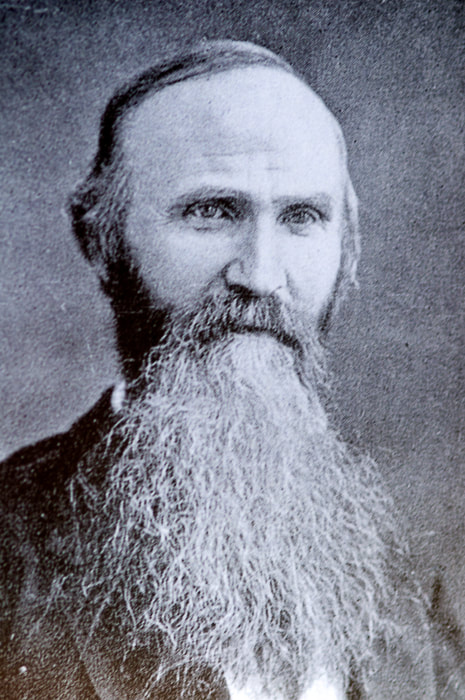

How did you imagine the appearance of Daniel McGilvary, Marion Cheek, Chao Inthanon and Louis Leonowens in Teak Lord? Compare with the images below.

The characters

Most of the characters in Teak Lord are based on real, historical people, although as I mention in the Author’s Note, I have taken liberties with their thoughts and actions, while attempting to portray characteristics that were noted by writers at the time.

How did you imagine the appearance of Daniel McGilvary, Marion Cheek, Chao Inthanon and Louis Leonowens in Teak Lord? Compare with the images below.

Unfortunately, I have never seen images of characters like Noja and Harry Stevens, though they were real people. I also have no photo of Moo (Phra Prachak), but that’s because he’s a figment of my imagination.

Tracking the Teak Lord

Part two: Exploring locations in the novel

The novel Teak Lord is largely based on historical facts, people and places, so a walk connecting locations mentioned in the story can be the perfect launch pad for anyone who fancies stepping back in time. This half-day stroll from the battlements at the northeast corner of Chiang Mai’s Old City to the grassy expanses of the Gymkhana Club, a colonial institution lost in time, makes for an enjoyable and informative wander through a bygone era.

The walk begins at Jaeng Sri Phum, the brick bastion in the northeast corner of the Old City. If you stand outside the moat, you can appreciate the wonderfully warped brickwork, which is surmounted by battlements from where the city was once defended.

In Teak Lord (chapter 5, Inside the walled city), though not mentioned by name, this is where Harry Stevens points out teak trees and bo trees to Marion Cheek, and where they witness a ‘trance dance’, as Harry calls it – a wild dance performed by spirit mediums. The trees are still there, and trance dances still occur on rare occasions, usually in the dry season, and are every bit as wild and colourful as in the past.

In Teak Lord (chapter 5, Inside the walled city), though not mentioned by name, this is where Harry Stevens points out teak trees and bo trees to Marion Cheek, and where they witness a ‘trance dance’, as Harry calls it – a wild dance performed by spirit mediums. The trees are still there, and trance dances still occur on rare occasions, usually in the dry season, and are every bit as wild and colourful as in the past.

From Sri Phum Corner, head east to the river, passing Talad Muang Mai, the city’s biggest fresh market, then turn right at a white stupa by the river and walk south. Cross the road at the Nakorn Ping Bridge and soon you will see a footbridge across the river from Warorot Market. Go up the steps and over this bridge, the original of which was built by Marion Cheek and was the first sturdy bridge across the Ping River.

The opening of Cheek’s Bridge is recorded in Teak Lord (chapter 47, Spanning the Ping), with a humorous outcome. Though Chao Inthanon, the local ruler, had financed its construction, he was scared to set foot on it, so Cheek had to cross the bridge with elephants to convince him that it was a reliable structure. Finally, the Chao was able to overcome his fear and ran full pelt across the bridge.

The opening of Cheek’s Bridge is recorded in Teak Lord (chapter 47, Spanning the Ping), with a humorous outcome. Though Chao Inthanon, the local ruler, had financed its construction, he was scared to set foot on it, so Cheek had to cross the bridge with elephants to convince him that it was a reliable structure. Finally, the Chao was able to overcome his fear and ran full pelt across the bridge.

Cheek’s teak bridge eventually succumbed to a constant bombardment of teak logs floating downstream, and the concrete structure here today is known as the Jansom Bridge.

On the east side of the river, cross the road carefully and step through the small back entrance into Wat Ketkaram (next to a red postbox), which leads to a typical wonderland of a Thai temple compound, with glittering eaves on the assembly hall and fearsome, mythical beasts on the wall of the ordination hall.

On the east side of the river, cross the road carefully and step through the small back entrance into Wat Ketkaram (next to a red postbox), which leads to a typical wonderland of a Thai temple compound, with glittering eaves on the assembly hall and fearsome, mythical beasts on the wall of the ordination hall.

Leave the temple by the main (east) gate, turning right and then left to the luxurious, atmospheric 137 Pillars Resort. The centrepiece of this relaxing retreat is a stilted teak house that was the office of the Borneo Company in the days when Louis Leonowens was their Chiang Mai Agent. The partially built house features in Teak Lord (chapter 46, The king of teak), when Leonowens makes a commentary about the race to be the champion teak trader.

Leonowens took over the job of Agent from Marion Cheek, who had been sacked for ‘cooking the books’. Some years later, Leonowens would suffer the same fate and go on to establish his own company, LT Leonowens Ltd, which is still in business today.

Leonowens took over the job of Agent from Marion Cheek, who had been sacked for ‘cooking the books’. Some years later, Leonowens would suffer the same fate and go on to establish his own company, LT Leonowens Ltd, which is still in business today.

This is an ideal place for a spot of lunch or an afternoon tea before continuing south on the east side of the Ping River, though there’s another chance for refreshment at the last stop, the Gymkhana Club.

The walk continues past the ample frontage of the First Church of Chiang Mai (though it’s actually the second), which was established by missionary Daniel McGilvary. A key character in Teak Lord, McGilvary is Chiang Mai’s best-known early foreign resident as he was responsible for the building of the city’s first schools and hospitals, though he made few converts to Christianity during his 50 years in the city.

The walk continues past the ample frontage of the First Church of Chiang Mai (though it’s actually the second), which was established by missionary Daniel McGilvary. A key character in Teak Lord, McGilvary is Chiang Mai’s best-known early foreign resident as he was responsible for the building of the city’s first schools and hospitals, though he made few converts to Christianity during his 50 years in the city.

South of the busy junction at Nawarat Bridge stands the real First Church of Chiang Mai, built by Marion Cheek in 1889. Its light blue, wooden spire is now part of the Chiang Mai Christian School.

About a kilometre further south, tucked away to the left of the road, is Chiang Mai’s Foreign Cemetery, where Daniel McGilvary and many other foreigners are interred. De Mortuis, a book explaining the backgrounds of the cemetery’s residents, is available here.

Don’t miss the statue of Queen Victoria, which stands at the northern apex of the site. It was brought to Chiang Mai to celebrate her Golden Jubilee in 1897, and the story of how it got to Chiang Mai, appears in Teak Lord (chapter 56, Victoria in Lanna). It once stood at the British Consulate on the other side of the river.

While in the cemetery, you might hear the thwack of golf balls or the plop of tennis balls in the adjacent Gymkhana Club, the final stop on this tour. Turn right out of the cemetery, then right again to the club’s entrance and go through to the terrace to enjoy a sweeping view of the golf course and cricket pitch from the shade of an enormous rain tree.

While in the cemetery, you might hear the thwack of golf balls or the plop of tennis balls in the adjacent Gymkhana Club, the final stop on this tour. Turn right out of the cemetery, then right again to the club’s entrance and go through to the terrace to enjoy a sweeping view of the golf course and cricket pitch from the shade of an enormous rain tree.

The club features large in Teak Lord – in chapter 38 (Birth of a colonial club), chapter 43 (Rumpus under the rain tree), chapter 52 (New laws, new taxes), and the first scene of chapter 56 (Victoria in Lanna).

No doubt the teak foresters whiled away many an hour in this delightful spot, sipping on gin and tonics or imported ales. If you have made it this far on our historic journey, treat yourself to a club sandwich and cocktail, flick through your copy of Teak Lord (or buy one here; on sale in the golf shop) to check references, then slip into daydreams of elephants dragging huge teak trunks through the forest to the river’s edge.

No doubt the teak foresters whiled away many an hour in this delightful spot, sipping on gin and tonics or imported ales. If you have made it this far on our historic journey, treat yourself to a club sandwich and cocktail, flick through your copy of Teak Lord (or buy one here; on sale in the golf shop) to check references, then slip into daydreams of elephants dragging huge teak trunks through the forest to the river’s edge.

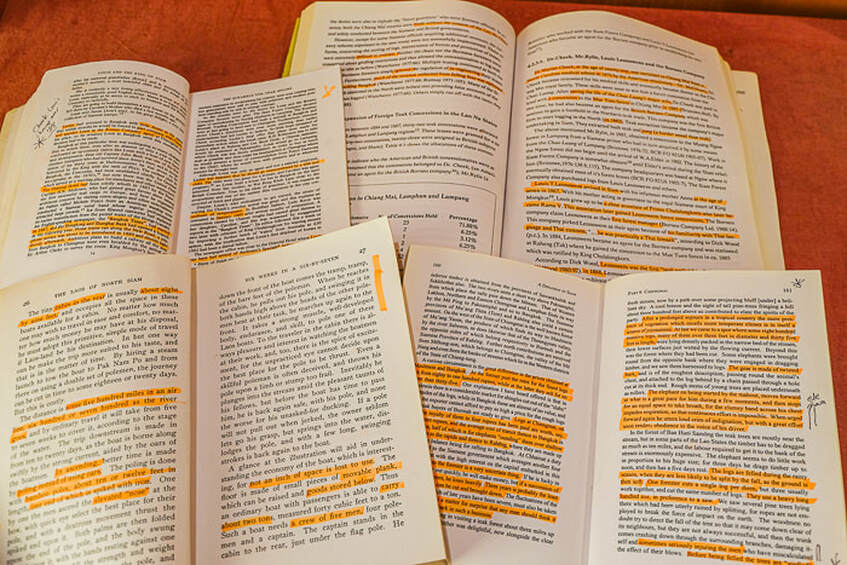

Tracking the Teak Lord

Part three: Fact and Fiction in the novel

Warning: contains spoilers.

One of the joys of writing fiction rather than non-fiction is that you don’t have to provide documentary evidence of all that happens in the book, as readers expect novels to be written from the imagination, not reality. However, as the saying goes, “truth is stranger than fiction”, and these days a great number of novels are “based on a true story”, as is my own.

One of the joys of writing fiction rather than non-fiction is that you don’t have to provide documentary evidence of all that happens in the book, as readers expect novels to be written from the imagination, not reality. However, as the saying goes, “truth is stranger than fiction”, and these days a great number of novels are “based on a true story”, as is my own.

The key phrase here is “based on”, as novelists are free to wander far from that base and create an altogether different version of what really happened. So it was with Teak Lord. For the first three-quarters of the book, I tried to be as true to the characters and events as I could, but for the last quarter, the tale took on a life of its own.

As mentioned in the Author’s Note at the beginning of the novel, I changed the sequence of some incidents to suit the plot, which also led me to give no dates after the opening phrase, placing the start in February 1875. I wanted the relationship between Cheek and Leonowens to be prominent in the story, though in reality, Cheek had been in Chiang Mai nearly ten years before Leonowens arrived. By giving no dates, I was able to introduce Leonowens fairly early in the book.

I took pleasure in the unlikelihood yet veracity of events such as Cheek’s visit to watch spirit doctors performing an exorcism, though in fact this scene is told almost exactly as it was recorded by Cheek himself. Cheek’s saving the life of Chao Inthanon’s wife may also seem unlikely, given local mistrust of his pills and potions, but the event is well documented and proved a key turning point in Cheek’s life, as from then on the Chao showered him with presents, such as a piece of land by the river and the pretty girl Noja, with whom Cheek went on to have an affair.

Since there are no reliable sources of dialogue conducted in those days, I used my imagination to create conversations while trying to be true to the personality of the characters as described by others. Thus the Reverend McGilvary is depicted as pious, Cheek seems greedy, both he and Leonowens are debauched at times, and Phra Prachak aspires to equanimity in all he does.

Phra Prachak is named after a Thai environmentalist monk whose conservation efforts earned him widespread recognition as well as enemies in the 1990s. Other monks who appear in Teak Lord are Ajarn Chah, who was a renowned meditation master of the 20th century, and Phra Dharmakosacarya, another highly revered Thai monk of the 20th century, who is better known by the name Buddhadhasa.

As mentioned in the Author’s Note at the beginning of the novel, I changed the sequence of some incidents to suit the plot, which also led me to give no dates after the opening phrase, placing the start in February 1875. I wanted the relationship between Cheek and Leonowens to be prominent in the story, though in reality, Cheek had been in Chiang Mai nearly ten years before Leonowens arrived. By giving no dates, I was able to introduce Leonowens fairly early in the book.

I took pleasure in the unlikelihood yet veracity of events such as Cheek’s visit to watch spirit doctors performing an exorcism, though in fact this scene is told almost exactly as it was recorded by Cheek himself. Cheek’s saving the life of Chao Inthanon’s wife may also seem unlikely, given local mistrust of his pills and potions, but the event is well documented and proved a key turning point in Cheek’s life, as from then on the Chao showered him with presents, such as a piece of land by the river and the pretty girl Noja, with whom Cheek went on to have an affair.

Since there are no reliable sources of dialogue conducted in those days, I used my imagination to create conversations while trying to be true to the personality of the characters as described by others. Thus the Reverend McGilvary is depicted as pious, Cheek seems greedy, both he and Leonowens are debauched at times, and Phra Prachak aspires to equanimity in all he does.

Phra Prachak is named after a Thai environmentalist monk whose conservation efforts earned him widespread recognition as well as enemies in the 1990s. Other monks who appear in Teak Lord are Ajarn Chah, who was a renowned meditation master of the 20th century, and Phra Dharmakosacarya, another highly revered Thai monk of the 20th century, who is better known by the name Buddhadhasa.

The significance of Buddhism in Teak Lord is probably the biggest deviation from historic reality to my own interests. Early Western visitors to Siam were unanimously “scathing” of Buddhist beliefs, as Cheek mentions in an early chapter of Teak Lord – Meditate for cool heart.

Yet Cheek seemed to be an open-minded character, and I do not think it beyond belief that he would take an interest in Buddhism, though his eventual ordination as a Buddhist monk in Teak Lord is perhaps stretching this point a bit. However, it did enable me to write a ‘feel-good’ ending in which Cheek and McGilvary finally overcome their differences.

In reality, Marion Cheek died, probably of cirrhosis of the liver, in 1895 in the Gulf of Thailand while on his way to Hong Kong for treatment, and now lies in a forgotten grave in the Presbyterian Cemetery in Bangkok.

A strong deviation from historical reality in the plot of Teak Lord begins with the chapter Birth of a Colonial Club, in which Marion Cheek pledges 500 rupees towards the purchase of the land on which the Gymkhana Club was to be built. You might notice that at the end of Part Two of Tracking the Teak Lord, the plaque bearing the names of the founding members of the club does not include Cheek. Since Cheek died in 1895 and the club was not formed until 1898, this is not surprising.

Yet Cheek seemed to be an open-minded character, and I do not think it beyond belief that he would take an interest in Buddhism, though his eventual ordination as a Buddhist monk in Teak Lord is perhaps stretching this point a bit. However, it did enable me to write a ‘feel-good’ ending in which Cheek and McGilvary finally overcome their differences.

In reality, Marion Cheek died, probably of cirrhosis of the liver, in 1895 in the Gulf of Thailand while on his way to Hong Kong for treatment, and now lies in a forgotten grave in the Presbyterian Cemetery in Bangkok.

A strong deviation from historical reality in the plot of Teak Lord begins with the chapter Birth of a Colonial Club, in which Marion Cheek pledges 500 rupees towards the purchase of the land on which the Gymkhana Club was to be built. You might notice that at the end of Part Two of Tracking the Teak Lord, the plaque bearing the names of the founding members of the club does not include Cheek. Since Cheek died in 1895 and the club was not formed until 1898, this is not surprising.

Two other characters grew large in my imagination during the writing of Teak Lord. One was George Woodward, whom I based on the character of Reginald Campbell. Campbell was the author of Teak Wallah, one of the most readable books about teak in Siam/Thailand, written in the 1920s. In chapter 16 of Teak Lord, Of girdling and ounging, Woodward gives a Campbell-like description of the entire teak logging process, from girdling to neaping, two peculiarly teak-related terms.

From photos of him, I imagined Campbell as an extremely proper type who never got dirty, even in the muddy teak forests. I was sad when I had to sacrifice him to allow Cheek an escape route from his predicament of being hounded by the Siamese government.

The other character I grew to like immensely was Harry Stevens, a man of whom I had only read a single reference as a one-time postmaster in Chiang Mai. I wanted a resident foreigner to befriend Cheek and explain some cultural quirks to him, so I developed Stevens as a ‘Cockney sage’ who introduces Cheek to everything from the ‘candlelit walk’ temple ceremony to the work of Charles Darwin and the use of a face mask, which these days is an indispensable piece of equipment for us residents of Chiang Mai in the dry season.

In sum, I hope I have painted a colourful and reasonably accurate portrait of Chiang Mai in the late 19th century, peopled by credible characters who reflect the interests of the era – namely piety, greed, debauchery and equanimity.

From photos of him, I imagined Campbell as an extremely proper type who never got dirty, even in the muddy teak forests. I was sad when I had to sacrifice him to allow Cheek an escape route from his predicament of being hounded by the Siamese government.

The other character I grew to like immensely was Harry Stevens, a man of whom I had only read a single reference as a one-time postmaster in Chiang Mai. I wanted a resident foreigner to befriend Cheek and explain some cultural quirks to him, so I developed Stevens as a ‘Cockney sage’ who introduces Cheek to everything from the ‘candlelit walk’ temple ceremony to the work of Charles Darwin and the use of a face mask, which these days is an indispensable piece of equipment for us residents of Chiang Mai in the dry season.

In sum, I hope I have painted a colourful and reasonably accurate portrait of Chiang Mai in the late 19th century, peopled by credible characters who reflect the interests of the era – namely piety, greed, debauchery and equanimity.

Set in the latter part of the 19th century in what is now northern Thailand, this period story of historical fiction is a masterful account of a time and place when smaller kingdoms, including Lanna and Siam (later to become Thailand) negotiated over the trades of teak and opium, along with the British Empire. Before reading this book, I had very little knowledge of this, other than being aware of the Chinese/British opium wars around this same period.

The author, who has himself lived in Chiang Mai, the largest city in northern Thailand, for 30 years. His incredibly meticulous research captures not only the area, but also the period, which is no easy task. As the reader, we gain awareness of this time and place through the main character, Dr. Marion Cheek, a medical missionary, who is brought there with the intent of promoting conversions to Christianity, but who loses interest and instead finds himself in the middle of the teak wood trade. Of note, Dr. Cheek is based on a real historical character.

In addition to Dr. Cheek, the author brings in significant number of historically accurate characters, such as Chao Inthanon and King Chulalongkorn of Siam. In the course of the story, you’re enveloped into a clearly chronologically and historically authentic tale in the middle of a time chronicled by Rudyard Kipling, and a place chronicled by Rodgers and Hammerstein in The King and I.

Several mighty and intelligent elephants also play a whimsical part of the storyline. For example, “It looks like someone has finished off their rice whisky, but no one will admit the blame,” responded Cheek. Just then, a loud rustling preceded the arrival of Look Bah in the clearing. The young elephant staggered from side to side, then after slumping in an ungainly manner on to one knee, she keeled over on to her side and promptly fell asleep. The men looked wide-eyed at each other, then burst out laughing together, realising that the culprit had just revealed herself."

In the process, we also learn much about the culture of Chiang Mai, Lanna and Siam, and about the teak and opium trades at that time. The personality and friendship of Cheek and Chao Inthanon feels playful and consistent with the historical record. One example is a cute scene when Cheek finishes building a bridge but the cautious Chao is afraid to cross it after his ceremonial cutting of the ribbon. Only after Cheek goes across it with three elephants does the ruler go across himself.

Overall, a wonderful read, which I highly recommend.

REVIEWED BY

Gregory Williams

The author, who has himself lived in Chiang Mai, the largest city in northern Thailand, for 30 years. His incredibly meticulous research captures not only the area, but also the period, which is no easy task. As the reader, we gain awareness of this time and place through the main character, Dr. Marion Cheek, a medical missionary, who is brought there with the intent of promoting conversions to Christianity, but who loses interest and instead finds himself in the middle of the teak wood trade. Of note, Dr. Cheek is based on a real historical character.

In addition to Dr. Cheek, the author brings in significant number of historically accurate characters, such as Chao Inthanon and King Chulalongkorn of Siam. In the course of the story, you’re enveloped into a clearly chronologically and historically authentic tale in the middle of a time chronicled by Rudyard Kipling, and a place chronicled by Rodgers and Hammerstein in The King and I.

Several mighty and intelligent elephants also play a whimsical part of the storyline. For example, “It looks like someone has finished off their rice whisky, but no one will admit the blame,” responded Cheek. Just then, a loud rustling preceded the arrival of Look Bah in the clearing. The young elephant staggered from side to side, then after slumping in an ungainly manner on to one knee, she keeled over on to her side and promptly fell asleep. The men looked wide-eyed at each other, then burst out laughing together, realising that the culprit had just revealed herself."

In the process, we also learn much about the culture of Chiang Mai, Lanna and Siam, and about the teak and opium trades at that time. The personality and friendship of Cheek and Chao Inthanon feels playful and consistent with the historical record. One example is a cute scene when Cheek finishes building a bridge but the cautious Chao is afraid to cross it after his ceremonial cutting of the ribbon. Only after Cheek goes across it with three elephants does the ruler go across himself.

Overall, a wonderful read, which I highly recommend.

REVIEWED BY

Gregory Williams